Revamping the “culture of sitting” with XT60 – Sadafumi Uchiyama (garden curator at Portland Japanese Garden, Oregon, USA)

Tatami – The bedrock of Japanese sensitivity

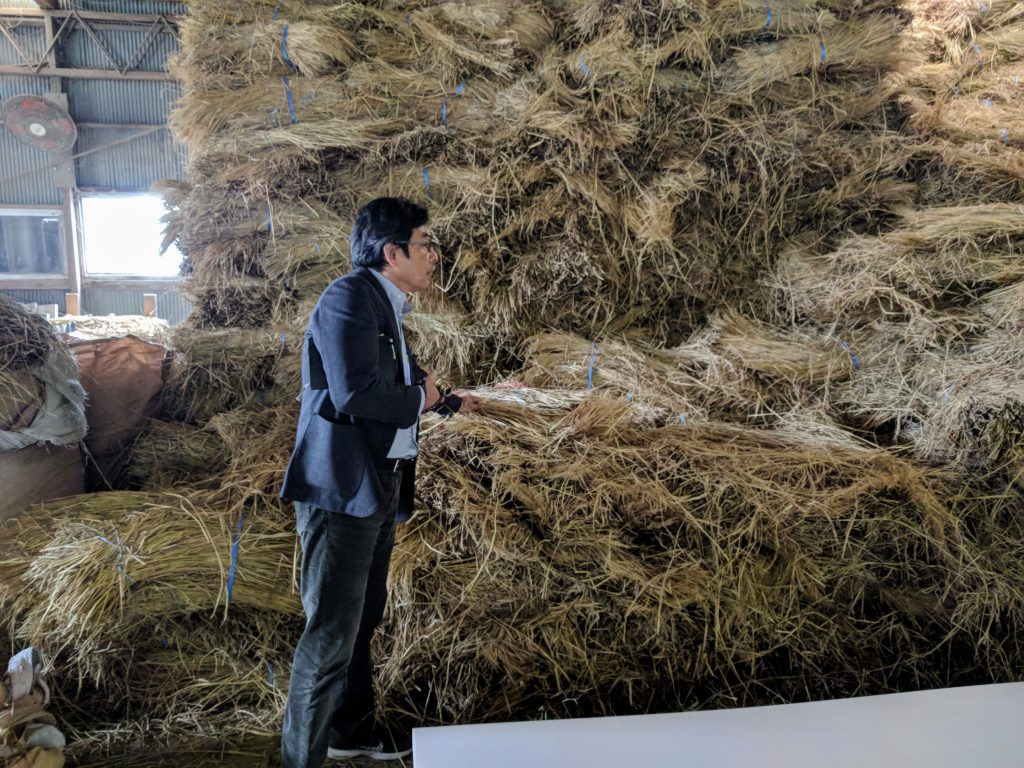

This design project forced me to reassess the “culture of sitting.” You see, when I took the project on, it was because what the president of Soushinsha, Hisashi Takahashi, was trying to do really got through to me: condensing the “culture of sitting” into the idea of tatami, and I found it incredibly intriguing. I was born and raised in Japan, and have lived in America for a long time, and I think that’s made me more aware of how the act of sitting on the floor is very much a consciously executed thing. When you sit on the floor, the open space over your head increases, making more room, and your line of sight changes, too. The feeling is also completely different, depending on whether you’re on wooden flooring or tatami. Also, the act of sitting lowers your center of gravity, and helps to instill a feeling of calm after the more strenuous activities of the body and mind during the day. And when it comes to Japan, the thickness of the tatami raises the level you are sitting on a little higher, which gives it a kind of ritualistic feeling. Sitting there makes it into your own private space where you can come back to yourself. I think you can say that tatami, the symbol of the “culture of sitting,” is the bedrock of Japanese sensitivity.

The square – Based on tradition and the human body

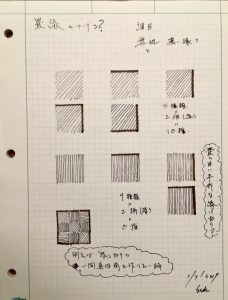

I based this design on the traditional Japanese measurements sun and shaku, which are a human scale: they’re based on the dimensions of the human body. These measurements have long been used in gardening and landscape architecture, so they didn’t feel unnatural or foreign to me at all. 1 shaku and 1 foot are about the same length: approximately 30cm. The meter measurement that we all usually use was devised more for mathematical convenience, and its length isn’t based on the human body. The basic size of a single tatami mat is 3 x 6 shaku (90cm x 180cm), but narrowing my focus to the concept of sitting led me to a square mat design of 60cm x 60cm. A completely square tatami may seem radical at first glance, but if you look at the checkered pattern in the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, you’ll see that it’s a necessary design that has been around for ages, since combining two squares results in a rectangle, or, the size of a door panel. Likewise, the XT60 can be used singly as a square, but can also be combined to make a rectangle. I guess you could say that the square was destined to coexist with the rectangle. (laughs) The square tatami was the result of me coming to grips in no uncertain terms with the idea of sitting. In doing this, I departed a little bit from the norm, while staying within the confines of traditional Japanese culture, by creating a 45-degree diagonal surface matting design. The shadows cast by this look beautiful when the mats are lined up with others. I added edging to some of the designs, so a large number of arrangements are possible, depending on how they’re laid.

After re-thinking the “culture of sitting,” what I actually designed is only half of the story, because tatami and gardens only come into their true meaning when they’re actually made use of. Once the XT60 is actually used it may go well beyond my original design intent, and I’m looking forward to seeing that other part of the equation.

Reflections on life going forwards

In these days of the coronavirus pandemic, all around the world we’re being implored to “Slow down” and “Stay home,” and in these troubled times you’re forced to think about fundamental things. I think everyone is experiencing going back to the basics of daily living, like cooking and eating at home and sleeping. When you come to think about it, though, that kind of environment can’t be created artificially. That’s why the priests of Eiheiji Temple (Fukui Prefecture) went to all the trouble of building it deep in the mountains. Now, in the COVID age, whether you’re on the plains or in a town, you’re in the same situation as if you were at Eiheiji.

Also, if you go on a trip somewhere and spend time in a different culture, sometimes it feels like your burdens are gradually stripped away. Don’t you think that the same thing can be said to be happening during this pandemic? In other words, given a chance to self-reflect, you get to feel a lightening of extraneous burdens. But of course, the important things, the essential things are left behind. There may be a difference in degree, but I think it’s a similar thing to the monks’ pursuit of truth in the mountains at Eiheiji. Being in an environment where you’re forced to confront yourself, to take stock of what you’ve done and think about what you’re going to do. And the world most likely won’t go back to how it used to be. Just like picking up what’s left from the aftermath of a fire and making a new life, I think the next few years will consist of retrieving what’s left of yourself after having gone through the pandemic, and making a new life with the things you can truly believe in.

(interview & editing: Chinatsu Shimizu, English translation: Richard Halberstadt)

Sadafumi Uchiyama – landscaper, gardener & garden curator at Portland Japanese Garden

Born 1955 in Fukuoka Prefecture, Kyushu Island, Japan, his family had been professional gardeners since the early 1900s, allowing him to study professional techniques from an early age. After participating in developmental cooperation projects in Tanzania and Yemen, he moved to the USA in 1988, gaining a degree and masters in landscape architecture from the University of Illinois, allowing him to combine aspects of Japanese gardening techniques with western landscape architecture principles. Active in a wide variety of private and public landscape projects, his representative achievements include gardens at Jackson Park, Chicago, Denver Botanic Gardens, Colorado & the Duke University, North Carolina. He is one of the founders of the North American Japanese Garden Association (NAJGA). Since 2010 he has been active all over America, working on private properties and commercial facilities, sometimes in collaboration with the famed Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. His publishing and speaking activities are centered in the USA, and he also teaches landscape design and practical application in universities and public Japanese gardens. In 2018 he was awarded the Garden Society of Japan Prize at the 100th anniversary celebrations of the Garden Society of Japan.

・Portland Japanese Garden

https://japanesegarden.org/